- Home

- John Cheever

The Journals of John Cheever Page 6

The Journals of John Cheever Read online

Page 6

•

Overcast, unseasonably cold day for the last of June. Depressing cocktail party. Worked at Moses and Clear Haven. Read “The Confidential Clerk” and some of “The Victim.” The set pieces about the city in the heat are fine. Nothing is in jeopardy. It is encouraging to see good work in this direction, and this direction is a record of the phenomenon of light; that we have always found heart in seeing a piece of wet paving; the trees whitened; the thrill of watching the 7:46 roll down the tracks this morning. Here are water lights and water smells; pristine economic and sexual energies. I think, Make some money to travel. Made some cherry jam last night. Four pots boiling on the stove. The fragrance of cherries boiling in sugar spread all through the house. Pleasant things.

Cocktails on Teatown Road; the tag end of the holiday. Mary worried about my gin-drinking distempers, but stayed too long. So we drink too much and become cross. Then to Fred’s, where everything seemed garbled. “Now lissen,” he said, “Langer is juss like McCarthy, and the reason for this is it’s a big goddam country, and the East is nothing buda patch.” Played some badminton; played some at dusk with the old lady. “He is very affable, now that he has sold the house,” she said. “Of course, we’ve always been very good friends, and my husband loved him.” Magnificent evening, with a changing wind; putting the rackets into the frame: a magnificent twilight. Then, not a collapse of propriety but of consecutiveness. Everyone wandering around with a glass of gin. “Stigaround, stigaround,” he says. “I’ll toss some gurry in a frying pan and we’ll have a bite. Stigaround.” I don’t want to eat gurry, I think, and rebuke myself for fastidiousness. Pissed on the driveway, and got my pants wet. Rose plaintively to every taunt. Bored and cross with Mary. Troublemaker. Wanted to get away. Pack my bag and take the midnight. Find some dark-skinned lady who would love me, or some old man. These interminable cocktail hours leave me with a sprained sense of charity and love; leave me spiteful and mean. But there is room for some spite in the picture. It will pass. Equilibrium in good shape, but still some romantic fantasies about us. If I should love my enemy, surely I should love my brother.

•

Back here with mixed feelings. I have known much happiness and much misery under this roof. The house is charming, the elm is splendid, there is water at the foot of the lawn and yet I would like to go somewhere else; I would like to move along. This may be some fundamental irresponsibility; some unwillingness to shoulder the legitimate burdens of a father and a householder. It seems, whenever I return, small in measure, dense in its provincialism. It is partly the provincialism in the air that makes me want to kick over the applecart. I long for a richer community, and who doesn’t. Woke up at dawn. Wandered around the lawn in my birthday suit. Enjoyed the pale sky and the monumental elm but I kept thinking, It is better in the mountains; it is better everywhere. I have been here too long.

•

There are pleasant things here, pleasant and unpleasant memories. The slum yards blazing with roses and hydrangea and later with dahlias. The people waiting, corner after corner, for the seven-o’clock bus to the station. The pretty girl with the kind of shawl that is fashionable today; the young executive in his uniform; the old woman dressed as a nurse, her cheeks painted a faded pink. There are all kinds of good things, but I might look into my resistance. I feel that this house, tree-shaded and standing at an east-west angle, has some depressing powers. I dread losing my equilibrium here, as I have done before. I see the charm in the valley and its houses—a sense of place—but I feel the force of provincialism within this charming front. This is friendly and clement, etc., but there is some conformism in the climate. There is perhaps the dread promise of permanence. I may be speaking of provincialism; I may be speaking of a deep strain of irresponsibility in myself; I may be speaking of that which in my marriage overwhelms me from time to time. Driving into the village I go along roads where I have been needlessly miserable and depressed. I like to think of a world much bigger than Shady Hill. I suppose every man does. I am not sure how it lies—Venice, New Hampshire, Martha’s Vineyard. I would like to settle and to preserve at the same time some breadth. The flaw in all this may be under my nose and yet I do not see it. We can live here through another winter, but I wish my anticipations were more cheerful. Perhaps I can make them so.

The midsummer night. Undressed, and walked in a towel down to the pool. The air was still and humid; the fountain and the pool lights were turned off. A single pattern of light came from the street through the leaves of the trees; in the distance, the lights of my own house. Waited, in a libidinous humor, for Mary. In the humid stillness, the throbbing of a ship’s motor sounded clearly from the river. It was some big craft—a tanker or a freighter, riding high. The sound of the screw deepened as she passed Clear Haven and then slacked off as she went upriver. Overhead, a plane crossed with all her gaudy landing lights still burning; her cabin windows lighted where thirty-four men and women, and a baby perhaps, sat in the febrile heat reading The Ladies’ Home Journal and Time. Upholstered, curtained, well-stocked with coffee, Dramamine, and Danish pastry—an image of ennui and meaningless suspense—she seemed to proceed very slowly below the large stars. The tree frogs sang loudly; so on will come the winter cold. It was the hottest night of the year. At my back, I heard some rats in the cistern. In the little skin of light on the water I saw a bat hunting. For a second everything that was familiar and pleasant seemed ugly. In the woods a cat began to howl like a demented child. The water smelled stagnant. I went in, swam, climbed out, and walked back over the grass. Religious things, superstitious things, what Veblen calls the devoutness of the delinquent—whatever it was, I seem to step into a pleasant atmosphere of goodness, a turning in the path that seemed to state clearly, Joy to the world, lasting joy. Awoke at two, smoked on the stones; still the loud noises of tree frogs. The cat drifted home. Many stars.

•

When I think of Mother, I think of the streets of Quincy, where she spent most of her life. It appears to be a small place, dark, a sphere among larger and more swiftly turning spheres; and to go from one to the other meant the severance of many moral and emotional ties. It was the common situation of having to break with one’s origins or live in despair. She is a woman of many excellent qualities. I think that she has not been secure in many of her immediate relationships. She seldom spoke of her numerous friendships without hinting at the power of loneliness. It was a powerfully sensual world; the smell of fires and flowers and baking bread and peaches cooking for jam and autumn woods and spring woods and the hallways of old houses and the noises of the rain and the sea, of thunderstorms and the west wind. This is a red-blooded and a splendid inheritance.

•

Quincy Journal. On the train downriver from Scarborough, much speculation. The feeling that Mother, with her natural impetuousness accelerated by some desperation or pain, has worked out her problems within such a narrow or egocentric sphere that the application of her principles to any broader field would result in the utter desolation of sexual anxiety. The sky and the water were overcast. At Tarrytown I saw a boat that had been sunk by the autumn rains. Boarded the one o’clock for Boston. Drank some whiskey in the diner with a cheerful businessman. The diner smelled of spoiled food. The linen was sordid; the waiters sullen. In the washroom the toilet was broken, and looking into the pot one saw the ties stream by. Outside, the autumn countryside; the brooks risen over their banks, and the sea, which seems, along the coast, to relate a sad, sad tale. I have made this journey thousands of times, and I suppose it is only natural, considering the past, that I should feel anxious; that I should revert to childish things; that I should be afraid not of any image but of shades, of that creation that lies in the corner of my eye. Back to the diner at the end of the trip for some more whiskey. The same smell of spoiled food. The waiters were changing their shoes—when the last woman had left the diner, their trousers. Outside, a fine blue in the west and a shower of rain. Only after drinking a little whiskey do

I feel the simple pleasures of travelling through the tag end of this rainy day. Oh, where are all my claims of wholeness? Where are all my gifts of judicious self-admiration?

To Quincy on the local; the flat industrial coast. This poignant, debauched countryside; street lights, mud puddles, and the evening star, and these sodden people—all but the pretty girls and the wild boys. Mother in bed with a stroke. Her speech thick, but her mulishness, her hearing, her appetite, and her intellect unimpaired. Josephine—a plain-minded woman—who has been engaged for twelve years to a sailor who has never brought his ship into a U.S. port. Some bad feelings, some good. The energy and the vigor of anxiety may fill a life with activity and invention, but it is an egocentric performance. Some supper; some whiskey; and Fred called. My failure at this relationship is one of the things I dread. My tendency is to call him a clumsy sorehead. Perhaps if I wrote about him as a sorehead it might help; it might take off some of the steam. I would like to call him a blundering, irresponsible fool, but I feel that one of my first responsibilities is to love him. A bad television show, and to bed. A room in which the ceiling is enamelled bright red and in which, I think, a dossal drape once hung. I can see a weak-minded pansy trying to redress this dreariness. Woke at four and wondered if such a neighborhood wouldn’t be full of voyeurs. But the crickets sing here, and the smell of the sea is fine. Concluded, half asleep, that all delight is an illusion; love is a shipyard tart, etc. The sweet ringing of iron bells; an ugly nightmare. Walked through th morning under the painful charge of anxiety; this utter desolateness. Thought of Mother’s ethical card house and the multitude of escape signs in this dreary place. A Viennese waltz plays in the supermarket; on the wall of the laundromat there is an English hunting scene; in the bowling alley there is a mural of some Indians, canoeing over the crystal waters of a mountain lake.

•

To church on Sunday; a fine autumn day although the foliage is not so bright this year. Raked and burned leaves with Ben. Much pleasure in this. The leaves a little damp, the fire moving in waves, each leaf taking shape in flame. As much smoke as a small battle. As it grows dark, the fire lights our faces; the trunks of the trees, gray ashes, flat, like a stain. The little boy, running barefoot over ash heaps, the warm ash heaps in the cool evening, as we used to do. Thought of last year’s passionate autumns where love obscured the crack in the ceiling and the dust under the bed and how this terminated in spitefulness and bewilderment. But these are not the things that will kill us. It is like the man who, suffering the agonies of vertigo, gets run over by a taxi. I have no time to waste and yet I waste my days. There is “The Journal,” “The Housebreaker,” and notes to be kept up, and “The Wapshots.” I ought to finish the journal today.

•

What we take for grief or sorrow seems, often, to be our inability to put ourselves into a viable relationship to the world; to this nearly lost paradise. Sometimes we see the reasons for this and sometimes we do not. Sometimes we wake up to find the lens that magnifies the excellence of the world and its people broken. Saturday was such a day. Planted some bulbs, drank some gin before lunch. But jumpy. Later to play some football, and here seems to be a step in the right direction; here is a means of putting ourselves into a relationship to the blue sky, the trees, the color of the river, and to one another. A dull dinner party among friends and neighbors. To early church. An unobstructed and splendid day. The S.s for drinks. I gave them “The Country Husband” to read. I can see where, in a social crisis, they might fail, and that this story may repel them. However, I love them. Late in the day, took a walk with the dog through the ruined garden. Found a dead cardina bird on the stones under the big arbor. A few scrubby chrysanthemums growing among the stones, and the bird’s bright blood color. The porous marble of the ornaments is still dark with last week’s rain. Took a look in the greenhouse. The fig trees are loaded with fruit but some of the leaves are blighted. This, like the dead, brightly colored bird—a bird I always associate with love and cheer—seemed vaguely portentous—foolishly so—but a part of the clearness, the coldness, and the beauty of the afternoon. But everything, the lights burning in the big house, the fine gold of the trees, seems to affirm our natural good health. This is beautiful, then, I think, the branches of the sycamore alley gleam like picked bones. This is beautiful then, I think, but is my good cheer rigged on a rich man’s park? There is unavoidable ugliness in the world—in its streets and faces—and would the text be the same if I were looking at a miserable tenement? I think it would be.

•

Anxious about being depressed on the way to Quincy and presently depressed. Down along the river here, and down along the Sound on the noon train, two Martinis and the charcoal-broiled, etc., and the interior dialogue with peculiar vehemence and in a space the size of a pinhead. Thinking of Coverly seeking for that precise moment where the visible and the invisible worlds bisect one another. Walked off the train at Back Bay, carrying my beaten suitcase. A lonely business, and I was deeply depressed by this time. How energetically the mind casts around for some escape from this conception of oneself as an ugly and useless obscenity; how stubbornly I refuse to pray. Walked across Copley Square; the sky was dark, my left foot hurt. Down Boylston Street past the stores that are all now cheap. Down to Washington Street—an eighteenth-century street, shining cheerfully with red neon light. Up a dark side street and then down around Scollay Square. Old and crooked places, melancholy lights, flophouses with armorial names, rat-toothed whores and old men. Up Joy Street and in a window I saw an old man and an old woman in a room lined with books. The room could never have had any sun, and it seemed to be where they ate, slept, etc. A depressing picture. Past chambers of old gentlemen and down Mount Vernon Street. Here are the traces of a city that, in the immediate past, had a well-regulated society, an opera season, débutante and fund-raising balls, shops, social contests, palaces, and dinner parties, but this core is broken and uninhabited now and the strength of the city has been drawn out into the suburbs, a kind of spawning ground that spreads out for thirty miles in every direction excepting due east, where the sea is. A provincial city. At nine o’clock the lights begin to go out. In a bar where I stopped for a drink, three soldiers picked up a whore, dated her, quarrelled among themselves about the bar check, and left the poor woman alone once more. People praising McCarthy in the bar. “Communists,” they say, “Communists, the world is full of Communists.” To the theatre, a provincial theatre. A play has stopped here on its way into New York. The old ticket-taker courteously asked me to put out my cigarette or suggested that I smoke it in the lobby; there was time. A hall of dusty mirrors, old red carpeting, much dark gilt, and everything supported by cupids in flight, by ropes of oak and laurel. They support the mirrors, they seem to hold the boxes in midair, even the balcony is suspended by this winged host of dingy gilt spirits. Pillars of chalcedony and an old curtain that sheds so much dust as it rises that it can be smelled. A bad play; applause. A pretty young woman with a date, taking off her coat and spreading it over the back of her seat, smiling up at the dark-gold host and the dim light that falls squarely into her face. How pure her pleasure is.

But that night, and I am reluctant to say so, there was no health in me, nothing better than patience. I see a world of monsters and beasts; my grasp on creative and wholesome things is gone. To justify this I think of the violence of the past: an ugly house and exacerbating loneliness. How far I have come, I think, but I do not seem to have come far at all. I am haunted by some morbid conception of beauty cum death for which I am prepared to destroy myself. And so I think that life is a contest, that the forces of good and evil are strenuous and apparent, and that while my self-doubt is profound, nearly absolute, the only thing I have to proceed on is an invisible thread. So I proceed on this. Quincy only deepens my depression. Why should I, a grown man, be thrown back so wildly into the unhappiness of the past? Where are those eruptive and clear springs of feeling that I claim to be able to count on? So back once mo

re on the train, abjectly miserable. The sweet water of inlets, salt inlets and fresh brooks, coming down to the sea. An Italian family waiting on a platform for a passenger who does not seem to have arrived. Wild high-school children travelling between Providence and Mystic. Thick speech, animal noises. Seeing the light of the city, my heart begins to rise. I seem to have over-scrutinized my dilemma. And as I am about to give it its seventy-first formulation (violence in my formative years cum uxoriousness cum anxiety) I stop. So this morning, zipping up my fly, I am cocky and happy. But I resent it that there should be parts of the world that have the power to do me so much harm.

•

To town with Susie for the annual Christmas journey. A very cold day, a pleasant girl of eleven with many damn-fool questions. The bows and rigging of ships, going upriver against the wind, white with ice. Many gulls, some ducks and geese. In the city a bitter cold and gale winds kept us from walking much. The tinkle of Salvation Army bells; the imitation leather of the Santas’ boots, their ill-fitting beards. To St. Patrick’s to see the windows; the smell of tallow and incense around the altar; my ideas on the papacy are only vaguely formed, but the cathedral does not seem to me a scene of depravity. To a bad Chinese restaurant for lunch, a place decorated with big stars made of mirrors and with red table tops scarred with cigarette burns. Spoiled meat. Then to Radio City Music Hall. I’ve written about this before and have nothing much to add. A cheerful folk rite without much depth of any kind. A medley of semiclassical music; some underplayed operatic selections; two first-rate acrobats and a patriotic finale—flags, and the whole cast singing “God Bless America.” The movie drenched in tears, and performed by men and women whose eyes are as big as skating ponds. You could drive a jeep down the shadowy division of the ladies’ breasts. Some clichés, but why put them down? My senses mightily offended by the bony charms of a dancer, her skinny legs, her tiny breasts, and her smile animated by the purest ambition. Rosemary Clooney—a young woman with an unusually deep front and a very heavy and unquiet mantle of yellow hair. Her features are far from fine. Her mouth is large and generous, so is her nose; her brow is wide. It is the kind of beauty that promises intractableness and deep and uncomplicated emotions, and that suggests a background—I don’t mean any place—I mean that mystical power of suggesting a horizon that most beautiful women possess. As for the skinny dancer, what affected me most were her shoulder bones. How these women with their toothy smiles, their manes of artfully dyed hair, seem betrayed, as they turn away from the camera, by the thinness of their shoulders—the bones of a hungry child.

The Wapshot Scandal

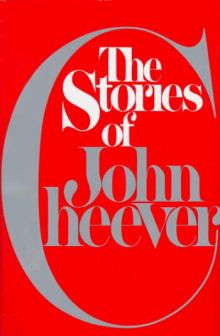

The Wapshot Scandal The Stories of John Cheever

The Stories of John Cheever Bullet Park

Bullet Park Falconer

Falconer The Journals of John Cheever

The Journals of John Cheever Oh What a Paradise It Seems

Oh What a Paradise It Seems Scott Donaldson

Scott Donaldson The Wapshot Chronicle

The Wapshot Chronicle The Stories of John Cheever (1979 Pulitzer Prize)

The Stories of John Cheever (1979 Pulitzer Prize)